This post is part of a series on short film production. Check out the other parts here.

Believe it or not, there are different opinions on the internet. I am not alone in the opinion that a script is the single most important piece of equipment in film-making. It is possible to make a terrible film from a good script, but it is almost impossible to make a great film from a terrible script.

I have started writing dozens of narrative scripts. I’ve finished a few. Congolese was the first short-film script where I felt confident that I had adhered to a number of script writing suggestions and had come away with a good script.

Themes and Ideas

The script for Congolese began with a number of ideas, each of which had their own challenges and merits. The first idea came from some research I had done for a feature length script a few years ago. That script featured the followers of an abusive homeschooling organization (whose leader was also abusive). In one survivor’s account she recalls her anger at her mother’s fervor for saving the African “savages” across the ocean while dealing out a level of abuse at home that was far more savage than what ended up on screen for my film. The theme of “Telescopic Philanthropy” is not original (is any story theme new?). Notably Mrs. Jellyby in Bleak House neglects her own family for the cause of an African tribe. Congolese is about Tabitha Fischer experiencing savagery in her own “civilised” family, and finding warmth and love from a strangers’ family. And not just any family.

The second idea idea about the script began when I met Hemedi in the summer of 2017. In the following months I learned some of his story; a Congolese refugee who lived for 15 years in Burundi waiting for refugee status. Through Hemedi, I met a few other members of the Congolese refugee community and was impressed by how easily warmth and friendship came from them, despite the unimaginable hardship most of them had experienced. The idea of a warm and loving African family that contrasts Tabitha’s own gave me an opportunity to partner with Hemedi, who had his own experience in filmmaking when he was in Burundi, and allow him to tell part of his story.

The last idea came from another fine piece of film storytelling I watched around the time I wrote the script. Get Out is incredible for a few reasons, but I was surprised at the amount of tension created in the film just by having a black male and white female in a relationship. I wanted the audience to worry about what Tabitha’s parents’ reactions would be if they found out about her relationship with Mwamba. These three themes/ideas provided the foundation for the story of Congolese, but short films need something else.

One unique challenge of making short narrative films is the difficulty of finding a story/character arc that will fit into less than 20 minutes. In that amount of time, it’s almost impossible to create the dramatic tension needed to make audiences care about the characters in the film. For this reason, most shorts end in some kind of dramatic twist; like the punch-line to a joke. The twist I picked for Congolese (spoiler alert: go watch it if you don’t want the twist spoiled) is also not an original idea. Mwamba and his mother and their warmth and caring only exist in Tabitha’s imagination. She invents his family to try to escape the horror of what she is experiencing at home. This idea is extraordinarily well done in Guillermo Del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth, only both the horrors and fantasy are more extreme in that case. If I had been able to produce Congolese as a feature length film, Mwamba and his mother would be real, but by making them imaginary and revealing it at the end of the film, the audience is given a sad and sudden closure to a story that was only beginning.

Structure

I’m a big believer in traditional structure in screenplays, although there are plenty of writers who are able to twist and distort them successfully. Therefore, I had written the story structure for Congolese early on. It is as follows:

Once upon a time, Tabitha Fischer lived with her conservative family hearing about the daring feats of missionaries bringing their civilized religion to the savages in Africa.

And every day she experienced savagery in her own home through the emotional and physical abuse from her mother.

Until one day, she had enough and stood up to her mother.

And because of this she ran away from home to some nearby woods where she had hidden some supplies.

And because of this she discovered her refugee neighbor from Congo, Mwamba, playing soccer in the same woods.

And because of this Mwamba invited her home to meet his mother and the two developed a friendship.

Until finally, Tabitha’s mother came looking for her, and discovers her hiding in a cave, imagining her relationship with Mwamba. Tabitha returns with her mother, back where she began.

If you’ve read Invisible Ink (or any number of other books on story structure) you might recognise my structure is not perfect. Neither is the script or its thematic content. As I mentioned previously, my goal was not to produce a perfect script or a perfect film, but to make something. Because an imperfect finished film has more value than a theoretical perfect one.

Rewrites

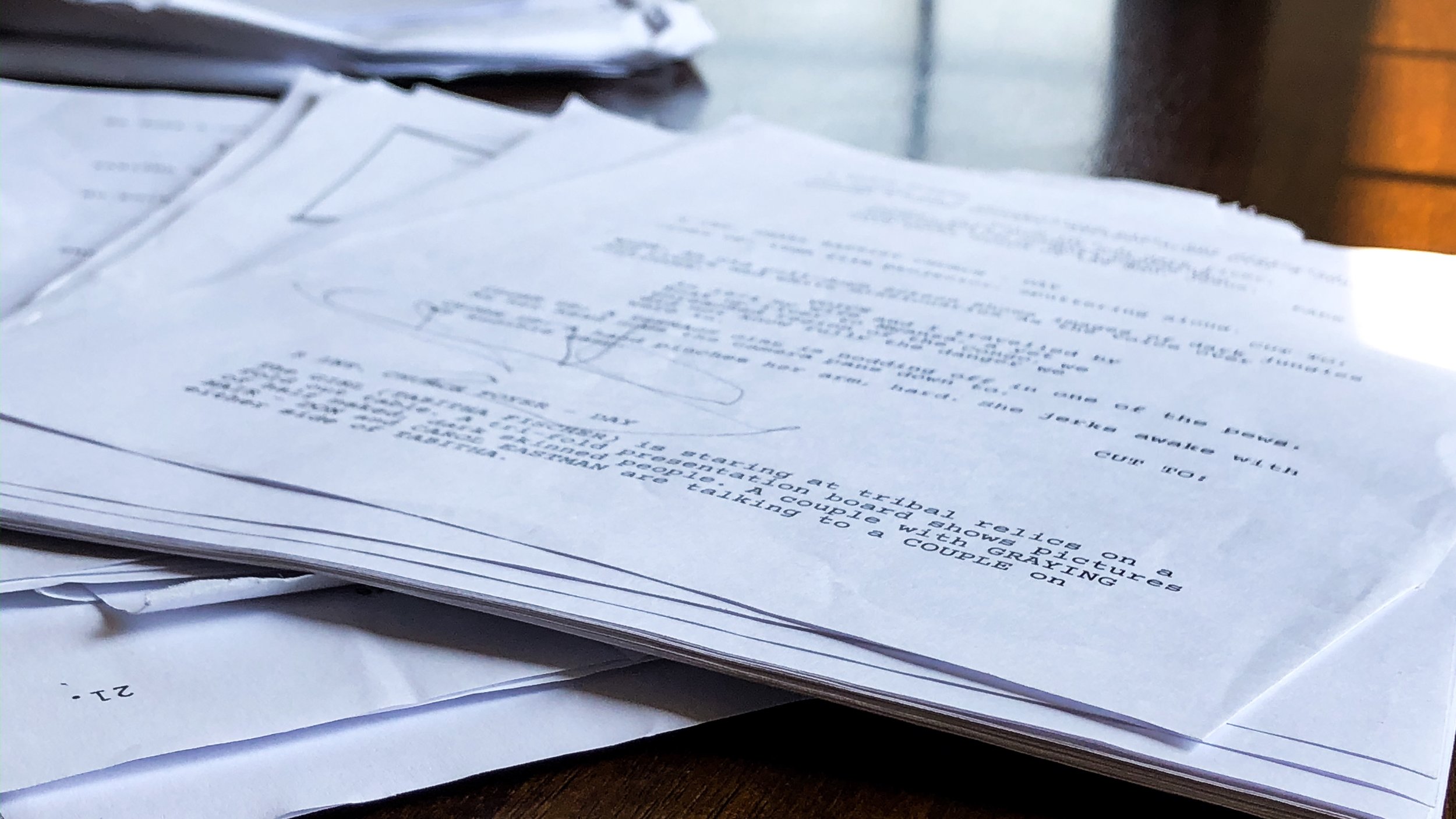

If you’re curious what my script rewrites looks liked from first draft to shooting script, I happen to have both copies for your comparison. Most of the changes to the script occur after Tabitha meets Mwamba and were rewritten by Hemedi. Ryan Whitener, who did our location sound, was responsible for the idea of the english lesson scene.

First Draft

https://www.dropbox.com/s/baejilwv1ox61r8/Congolese%202%20blog.pdf?dl=0

Shooting Script

https://www.dropbox.com/s/w3yma0cf3l4gkhm/Congolese%20SHOOTING%20SCRIPT.pdf?dl=0

Looking back, much of the first half of the script stayed as it was written in the first draft. Some rewrites were done in the editing, but for better or worse, most of the script ended up on screen at the festival.

As I mentioned, it is not a perfect screenplay, but it turned into a finished film. I even learned a few things along the way. I learned that you don’t need very much abuse to happen on screen for the audience to accept that a character wants to run away. I ended up cutting one of my best executed scenes from the film because of that error.

I learned that putting complicated prop and makeup details in the script of a low budget short film isn’t a great idea, especially if those elements are critical to the story making sense. The belt hit and the injury it caused were both critical elements in the script that motivated why Mwamba might invite Tabitha home and why she might agree to go with him. I had a hard time executing both the hit and the injury which I will talk about later.

I still have a lot to learn about writing, but I remain convinced that a good script is the best head-start you can have toward making a good film.

What are your approaches to script writing for a short film?